Are you still enjoying go-with-the-flow, fun and relaxed reading with your child?

Click on the link below to listen a dad and his little boy enjoying a book together:

https://www.instagram.com/p/B7JlCyNhkdIXkWEgmkswqp7YCe_P0fyd8lPcFk0/

Has your child started bringing decodable books home from school?

Several years ago, I put together the following set of videos. They demonstrate some teaching strategies for parents and children to try when reading together at home.

Book introduction

When introducing new decodable books to trainee readers, my aim is to draw their attention to the print as quickly as possible.

My goal is for every child I teach to grasp the concept that letters spell sounds in words. I reinforce this concept through the vocabulary I use, “Can you find the word that spells ‘dog’?'”

My intention is to build a strong connection between reading and spelling.

Introducing a book to a beginner reader is time well spent. The purpose is to provide footholds within the text, so that when we read the book again the child can confidently navigate his way through the text, as independently as possible. I give opportunities to enjoy several rereads, on separate occasions, each time working to improve the fluency and sound of his reading.

In Book Introduction 2, I keep encouraging the reader to be independent. He works hard to segment (sound out) the word ‘and’, but shows a tiny bit of reluctance about blending the sounds. Off camera, he looks up at me with eyes that say, “Please! Just tell me the word, Julia! Can’t you see how hard I’m working?”

It’s possible that the extra ‘uh’ sound, which he is adding to the ‘d’ at the end of the word, is causing him confusion. My prompt: ‘You try‘, passes the problem-solving responsibility back to the reader, while I stand by to model a pure ‘d’ sound (in place of ‘duh’) should I need to… but he quickly and capably rises to the challenge to go it alone.

After the hard work of decoding the words on the page, I encourage the reader to put it all together. As a reader begins to understand capital letters and sentences, I use the prompt, ‘Now put the sentence together again.’

It is important to remember that the decoding of each word is just one part of the reading process. I am also actively seeking opportunities to develop the sound (fluency and phrasing) of the reading. I also need to pay close attention to ensure the reader is understanding what he reads (comprehension).

At the end of Book Introduction 2, my reference to the picture is designed to encourage the reader to make links and access as much meaning as possible from the words he has read.

In Book Introduction 3, we continue to see promising signs of progress in the child’s reading development:

+ he is consistently working from left-to-right through the word, as he segments and blends (if he wasn’t, I might use a friendly prompt like, ‘Always start with the first letter!’ and the slow reveal technique if he still needed help);

+ he is confidently matching letters to their corresponding sounds;

+ and he’s doing an excellent job of differentiating between the letters ‘b’ and ‘d’ (which can often cause confusion).

The young reader seems to experience some difficulty with the word ‘bad’. The additional ‘uh’ sound he is currently adding to ‘b’ and ‘d’ is complicating his attempts to blend the sounds. When I step in and model the pure sounds for him, he is able to blend successfully. More opportunities to hear these pure sounds being modelled, and more opportunities to practise producing these sounds himself, will help his word attempts.

Finger-framing

My aim is for children to grow in independence as readers. In this clip, the reader slows down as he reads, which seems to show he is aware that something in the sentence isn’t quite right.

I use a prompt at the end of the sentence to encourage him to have another go at finding and fixing the problem for himself: “Try that sentence again.” (This can also be a helpful way of assessing the child’s understanding of the concept of a sentence – do they return to the beginning of the line? a random capital letter? or are they able to identify the point at which a sentence begins?)

I begin to reinforce the concept that letters spell sounds in words through the vocabulary I use, “Can you see the two letters working together?”

I then use a technique called ‘finger-framing’ to highlight the focus letters, ‘ai’, and I give my reader the corresponding sound, /ay/. I’ve found this can be a more effective way than simply telling the child the problem word. It gives the reader a foothold, whilst encouraging the child to take the initiative to independently use and apply the given information.

Listen to the confidence in the reader’s voice return, as he solves the problem and corrects the sentence.

Slow reveal…

The ‘slow reveal’ technique helps the child to work through a word, by focussing on one letter-sound correspondence at a time.

In this blurred video clip, the reader has already read 14 pages and is flagging a little. He remembers the word ‘hums’ from reading this book previously, but recognises that ‘hums’ doesn’t work in the sentence. He goes back to check the letter detail (and I am silently cheering him on, but careful not to interrupt his thought processes). I then use the slow reveal technique to scaffold his attempt, steadily revealing one letter-sound correspondence at a time (please note: I do not reveal the ‘e’ and ‘r’ as separate letters, but as ‘er’ because they are working together to spell one sound).

My aim is for the reader to take the initiative. My role is to steer him back on track. He does a good job of segmenting the word, but struggles to blend the sounds. I’m aware that he’s close to saturation point now – he’s worked so hard already – but I still want him to be as independent as possible. I segment the word for him and he confidently blends the sounds and carries on. You can almost hear the ‘KERCHING!’ as the penny drops.

Swift, specific praise

When we’re learning something new, we need helpful feedback along the way. Beginner readers need swift, specific praise. “Good reading!” and “Well done!” aren’t always enough. Ideally, we need to leave them in no doubt as to what is ‘good’ about their reading and exactly what it is that they’re doing well.

This video clip isn’t the best example of specific praise (I could have been more specific about why the reading was sounding ‘great’), but it is a lovely example of this reader beginning to use the rise and fall in his voice to capture the interest of the listener.

Next steps:

+ when the reader is reading confidently, wean him away from finger pointing in order to help improve the sound of the reading. (I use prompts such as, ‘Try the next page without using your finger. Get your eyes to do the work.’ )

+ encourage the child to read at a good pace – model reading a sentence with fluency and phrasing, then let him try. (In this clip, I prompt the reader to ‘go a little bit faster’, not because I want to hear rushed, garbled reading where all sense is lost, but because I’m aiming for a flow and fluency to the sound of the reading. This area of development needs frequent modelling and practice.)

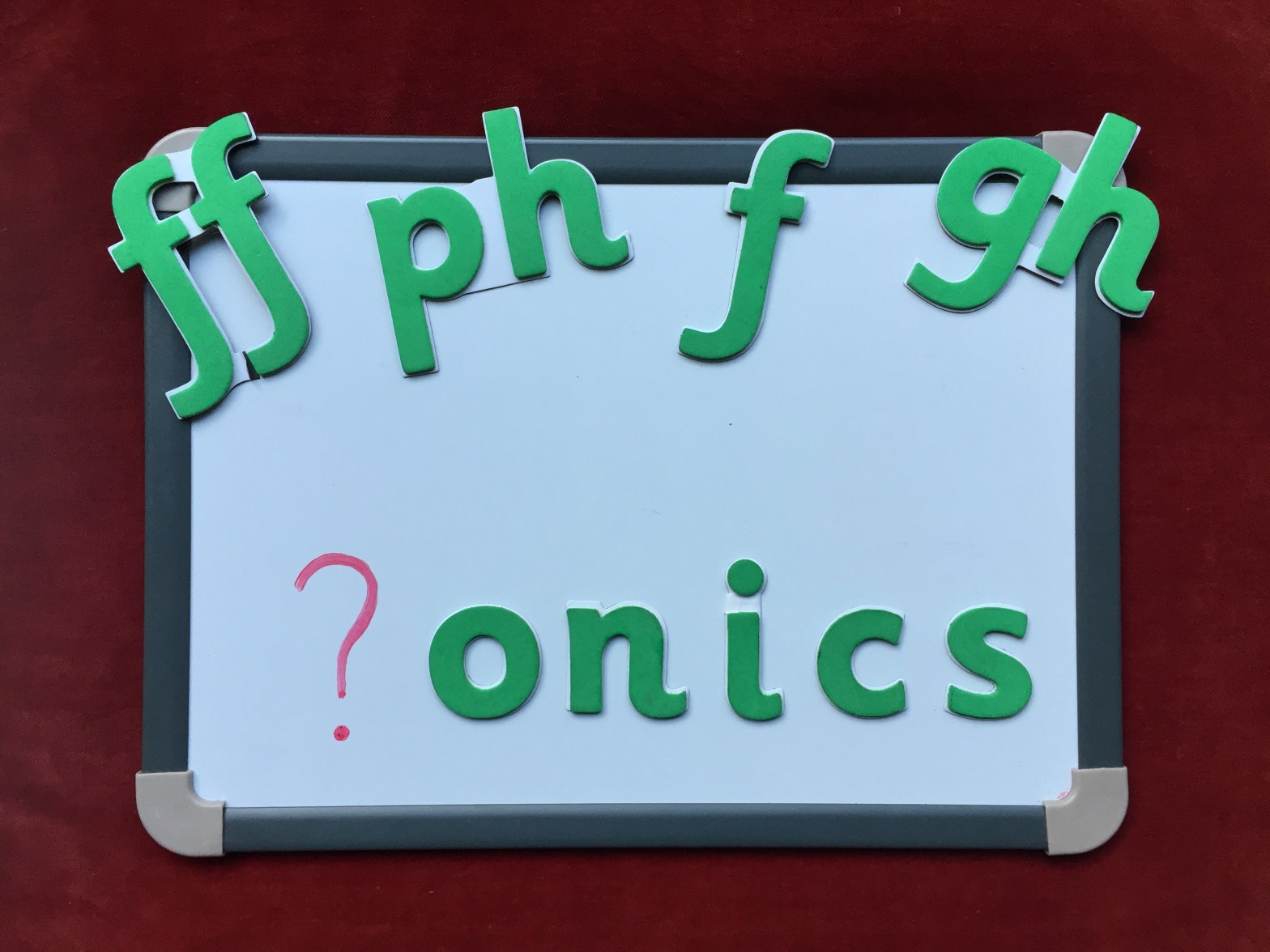

Letters spell sounds in words

I believe developing readers and writers need to grasp the concept that letters spell sounds in words.

I admit, I overdid it when I interrupted the reading again for the /oo/ ‘ough’ in ‘through’.

I wanted to demonstrate how this concept can be helpful for readers, even in their attempts to decode more complex words. I encourage the reader’s independence by giving her the responsibility of locating the four letters working together to spell /ay/ in the word ‘straight’ – and then the four letters working together to spell /oo/ in the word ‘through’.

The reader is preparing to take the picture book home to read to her little brother. Once we have worked on decoding, we begin to move onto the sound of the reading. Plenty of patient practice is required.

Children need many, many opportunities to hear stories read aloud with clear phrasing, fluency and expression – and equally as many opportunities to safely experiment with their own voices, as they learn to use them to engage and entertain their listeners. This young reader showed an increased level of self-consciousness, no doubt due to the presence of the camera. My hope is that she was able to relax, experiment and play with her voice a bit more when she and her brother enjoyed the story together at home later that week.

(I’m sorry my films aren’t better quality and I hope nobody will dismiss my contribution when they see the old Biff, Chip and Kipper book.)

Hi Julia,

I have finally just read this and watched the videos.it was really helpful and supportive for the work I continue doing at Bosbury.

I’m really pleased to hear that, Maggie.