In October 2022, I published a series of 6 short blog posts. Writing and publishing them gave me the opportunity to think out loud about where I’d been, where I was, and where I wanted to be. I wondered if they’d be easier to access if they were altogether on one page, so here they are:

1

When I repeatedly expressed my concern about the lack of provision for the needs of individual children during the years I spent teaching in schools, I increasingly met with the response, ‘It is what it is’. The phrase appears to mean a whole lot of different things to a whole lot of different people.

The varied definitions on Quora are a case in point. Carol Cotton’s interpretation feels like a good fit for a busy school leader with a heavy load of responsibilities, who is looking for a polite – but effective – way of saying:

“…don’t waste your time (or mine) trying to “go deep” into analysis of something or figure out how to change or get around it. It is what it is, get over it, and don’t bend my ear with yer belly achin’ about it.”

Carol Cotton, Quora

Nancy Erdmann’s translation reminds me of staff in schools, who have found the phrase to be a helpful coping mechanism. They need to survive in a system they know is broken. They’re desperately trying to preserve some head space and energy for their lives outside of school. A sense of resignation to decisions seemingly beyond their control allows them to switch off when they need to.

“It is what it is,” essentially means “That’s life. You can’t change this situation, problem or reality. No sense talking about it or getting too stressed out. You have to make peace with reality and keep going.”

Nancy Erdmann, Quora

Taylor Maness, however, argues that the saying can lead to a toxic and harmful state of mind:

‘This phrase is worrying because it is far more than an autopilot response people use; it is a complete mentality. The basic meaning behind these words is that we are unable to change our circumstances. All situations are concrete and any attempts we make to fix them would be pointless.

This is an incredibly destructive mindset to have. We have a basic need to feel a sense of control over what happens in our lives, and deprivation of this need could lead to heightened anxiety and even depression…’

Taylor Maness, ‘Why “it is what it is” is a toxic saying’

As the teacher recruitment and retention crisis deepens, how many teachers have met the undercurrent’s pull with a pervading powerlessness? How many have found their sense of agency suffocating in a toxic ‘it-is-what-it-is’ culture?

But the focus of this series of blog posts isn’t the needs of teachers…

2

From my tiny corner of the world, from my minute circle of influence, from my blurred understanding of the situation, I am using the voice I have been given to speak out for the needs of our most vulnerable children.

“We must speak with all the humility that is appropriate to our limited vision, but we must speak… We are called to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation…”

Martin Luther King Jr speech, ‘A Time to Break Silence: Declaration against the War in Vietnam’

These children are the Timothy Winters of today and I am deeply concerned for them.

‘The Welfare Worker lies awake

‘Timothy Winters’ by Charles Causley

But the law’s as tricky as a ten-foot snake,

So Timothy Winters drinks his cup

And slowly goes on growing up.’

A recent tweet drew my attention to the Yorkshire Bylines article, ‘School, stress and poverty: a psychobiological reflection’ (2022), written by Dr Pam Jarvis:

Dr Jarvis pinpoints the stark, underlying factors in the lives of children caught up in (but too often slipping through) the net of current catch-up agendas.

“Children raised in poverty … are faced daily with overwhelming challenges that affluent children never have to confront, and their brains have adapted to suboptimal conditions in ways that undermine good school performance” (Jensen, 2009)

‘Children who live in households where insolvable problems constantly arise have to use cognitive resources to process these. Consequently, they have less ‘mind space’ (or bandwidth) to give to other things, including learning…

‘Cortisol disturbances in young children can lead to suppressed growth, anxiety, depression and less memory capacity available for intellectual development because their resources are diverted elsewhere to cope with what the brain processes as a series of immediate threats that arise in the home environment…

‘No amount of extra input can compensate for a brain that is too loaded with stress to learn. In fact, it may create precisely the opposite effect by increasing the stress that is affecting the child’s daily life.’

Dr Pam Jarvis, ‘School, stress and poverty: a psychobiological reflection’ Yorkshire Bylines, 01/22

When I was teaching, did I do enough to ensure my ‘extra input’ wasn’t ‘increasing the stress’ experienced by young children? Did my rafts of well-meaning learning interventions create extra obstacles to the flow of progress for them?

Last year, I taught full-time in a reception class of 30. In regular Pupil Progress meetings, school leaders and I discussed the needs of children who were not ‘on track’ to meet Age Related Expectations by the end of the academic year. Consequently, I programmed targeted interventions to ‘meet the needs’ of these individuals.

But did they?

3

I’m currently unemployed and, when I’m not trawling through job pages or writing applications, I’ve been able to read widely and let my thoughts run free. A question in a recent post from Professor Alison Clarke on her ‘Slow Knowledge’ blog prompted me to reflect more deeply on my EYFS practice last year, ‘In what ways does the future overshadow the present in young children’s lives in ECEC (Early Childhood Education Centres)?‘.

For children in my reception class, I believe my interventions (which were designed to meet a future goal) risked casting a shadow over their EYFS experience. If I’d recorded how many times each child’s play was interrupted over the course of the year, I have no doubt I’d have been shocked by how frequently the ‘not-on-track’ child was interrupted, compared with their ‘on-track’ peer.

Tidying up last week, I found notes I had taken from an Early Excellence podcast in October 2021. They drove home to me just how much these interruptions matter:

‘ Allow for long periods where children can create and explore their own ideas and learning. When children are interrupted regularly, they get used to not being engaged and not seeing an activity through to completion.’

My notes from: New to Teaching in the EYFS Part 2, an Early Excellence Podcast

I’d like to think that, if I had been more alert and aware of the risk of interruptions to play, I would have been more proactive in timing necessary interventions and, wherever possible, more skillful at incorporating interventions into the child’s ongoing, uninterrupted play.

I qualified as a teacher in 1992. I’ve carried out countless interventions since then. In hindsight, how many were interruptions?

I had good intentions for my interventions. I know that.

4

There will always be children for whom classroom instruction is not enough and for whom extra support must be provided. After training as an Every Child a Reader (ECaR) teacher in 2010, my last decade has been built on the value of literacy interventions. When the Herefordshire County ECaR funding ran out, I returned to full-time class teaching.

As a class teacher, I made a contribution to meeting the needs of children with specific learning difficulties, but I knew I wasn’t enough. As a literacy intervention teacher, I pulled out all the stops to make weekly 30 minute lessons count, but I knew I wasn’t enough. I worked in children’s homes, where I encouraged parents to sit in on lessons, so I could model evidence-informed teaching and learning strategies. I felt I was making a positive difference – but only for families who were able to pay.

When Jesus said, “The poor you will always have with you,”…

…was he saying, ‘It is what it is,’?

For the vast majority of children, the support they receive from home will make a significant and lasting impact on the child’s reading journey. The books their families provide them with, the bedtime stories they share, the interest their parents show in the contents of their school book bag, the times they see their own parents curling up with a good book… are investments in the child’s future success as readers. But when, for whatever reason, parents are unable to give their children these advantages, what then?

‘It’s lovely when parents work alongside schools to facilitate the journey to literacy, and I encourage the recruitment of keen parents to help out in this way. But it simply cannot be one of the make or break factors. We have to inoculate our students against circumstances not ideal for literacy acquisition. Approaches that are in some way reliant on home life only perpetuate social disadvantage.’

Lyn Stone, ‘The Home Learning/Literacy Myth’

Last Thursday, I tuned into Herefordshire Council’s live cabinet meeting where the soberingly ‘inadequate’ Ofsted report of Herefordshire’s Children’s Services (July 2022) was discussed. When the DfE Children’s Commissioner, Eleanor Brazil, addressed the meeting, she assured the councillors,

‘…I come with no assumptions about what the solution for Herefordshire might be… but first and foremost, my role is about supporting the council and its partners to improve things for your most vulnerable children, at pace.’

Herefordshire Council Cabinet 29/09/22 (27:28)

Many believe that when Jesus told his followers, “The poor you will always have with you,” he was leading them back to a well-known passage of scripture:

‘If among you, one of your brothers should become poor, in any of your towns within your land that the Lord your God is giving you, you shall not harden your heart or shut your hand against your poor brother, but you shall open your hand to him and lend him sufficient for his need, whatever it may be …

For the poor you will always have with you in the land. Therefore, I command you, ‘You shall open wide your hand to your brother, to the needy and to the poor, in your land.’

Deuteronomy 15:7-11

There are times when I feel utterly overwhelmed by the vast complexity of desperate need in this diseased and broken world. When I look into my own wide-open hands, I’m tempted to despair. What do I have to give in the face of so much need?

5

In this period of unemployment, I have time on my hands. Am I using it wisely? Was Carol Cotton right in her ‘it-is-what-it-is’ advice to not, ‘waste time trying to “go deep” into analysis of something or figure out how to change or get around it.’? Or was John Stuart Mill speaking truth when he encouraged men (and women) ‘to use his [her] mind on the subject‘ and ‘form an opinion‘?

“Let not any one pacify his conscience by the delusion that he can do no harm if he takes no part, and forms no opinion … because he will not trouble himself to use his mind on the subject.”

John Stuart Mill’s 1867 inaugural address, University of St. Andrews

In last Thursday’s Herefordshire Council Cabinet meeting, Councillor Diana Toynbee opened the discussion of the report into Herefordshire Children’s Services. As she outlined some of the progress that had been made since the inspection and the foundations that are being established, Councillor Toynbee stressed,

“This work is all about relationships.”

Herefordshire Council Cabinet 29/09/22 (24:37)

Last month, a tweet introduced me to an article by Dr Jamila Dugan, ‘Co-Constructing Family Engagement’. The insights she shares feel like a breath of fresh air.

‘All educators wish to create strong relationships with the families we serve. But we may not realize that some of the common practices we use to build those relationships actually get in the way of true partnership…

Dr Jamila Dugan, ‘Co-Constructing Family Engagement’

Dr Dugan uncovers the factors that can prevent families from fully engaging with schools,

‘Families who have been marginalized have little reason to trust educators. Not because we have bad intentions or wish to do wrong by children, but because our system has shown time and time again that schools can be places where students at the margins can experience great harm.’

Dr Jamila Dugan, ‘Co-Constructing Family Engagement’

She holds a safe space for educators and families, where it’s okay to not have all the answers, while encouraging us to work together to build two-sided relationships, where everyone’s voice is heard and valued.

‘There is power in educators acknowledging that they have not yet figured out how to best support each or all the students in front of them. We don’t always know how to hold high expectations, provide support, and nurture positive attitudes, and because of these gaps we are prone to make mistakes. This is why we need family partnerships. This is why relationships matter from the beginning.

The underlying belief is that to best support a child, we must get to know each other, create a shared picture of student goals and needs, and engage in collaborative activities like problem solving.

…there’s a power in admitting you don’t have all the answers.’

Dr Jamila Dugan, ‘Co-Constructing Family Engagement’

There was a time when I thought I had the answers. I remember extolling the virtues of a certain reading intervention programme, quoting the ‘facts’ and ‘figures’ I had imbibed, intent on ‘proving’ its success rate to anyone who would listen. Before I even began my in-service ECaR training, I religiously believed and proclaimed the ‘research evidence’ – without engaging in any level of critical analysis. My husband’s academic studies introduced me to aspects of critical thinking which continue to serve me well.

Conversations are inevitably one-sided when somebody is convinced that they hold the answers. At the beginning of my period of self-employment as a literacy intervention teacher (2013-2019), my training and experience had already equipped me with a significant amount of knowledge and understanding of how children learned to read and write, and what I could do to support their learning process. But I didn’t have all the answers and there’s little evidence to show that my methods opened up collaborative, problem-solving conversations with families and schools.

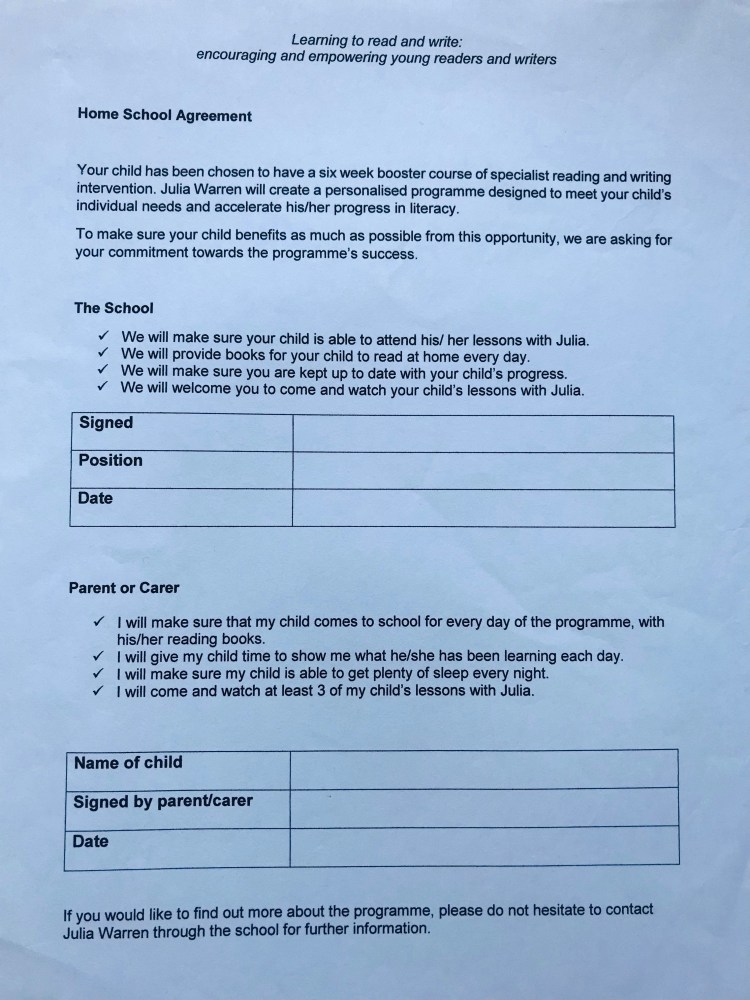

Take my contract, for example:

There’s not a lot of trust involved in getting somebody to sign a contract to agree to do what you say, when you say it, is there?

‘Your child has been chosen to have a six week booster course of specialist reading and writing intervention.’

Parents: Why?

‘Julia Warren will provide a personalised programme designed to meet your child’s individual needs and accelerate his/her progress in literacy.’

Parents: Who’s Julia Warren? What does she know about my child’s ‘individual needs’? What if I disagree that ‘accelerating’ my child’s ‘progress’ is in their best interests?

How can families and educators build two-sided conversations, where we can actively learn from each other and properly collaborate to deliver the best outcomes for everyone?

Dr Jamila Dugan advocates the power of small, meaningful interactions in establishing trust and mutual respect. She promotes authentic dialogue, where families and educators can grow to understand each other’s expectations and priorities.

‘When families and educators do come together and brainstorm answers around a central question in a way that nurtures dialogue and shared ownership, the solutions are always richer. And when we create those opportunities with families who have been othered or minoritized in mind, we have more opportunities to increase inclusivity.

Dr Jamila Dugan, ‘Co-Constructing Family Engagement’

I’m uplifted by the possibilities of all that Dr Jamila Dugan suggests.

6

‘Finishing is better than starting.

Patience is better than pride.’

Ecclesiastes 7:8

As the 2022 summer term began, I took time to create a goal to give me clarity of purpose for the final weeks of my last job as a classroom teacher. I kept my intention in mind, ‘to work closely with the children, their parents and my colleagues to provide a strong, secure foundation for us all to build on’, and it helped me to focus my attention on what was important.

Individually, in groups and as a class, the children and I frequently discussed the move to Year 1. I reminded them of how, at the start of reception, they had all come together for the first time. I encouraged them to be a strong team, to show friendship and kindness by supporting each other and asking for help when they needed it. I taught them a song (which my granny used to sing to me, long before Barney & friends filmed their version),

‘The more we are together, together, together,

The more we are together, the happier we’ll be,

My friends are your friends, and your friends are my friends,

And the more we are together, the happier we’ll be.’

(to the tune of ‘Did you ever see a lassie?’)

After the whole school ‘move-up morning’, I used our interactive whiteboard to display photos of the children in their new classroom with their new teacher and teaching assistant. I underlined all the potential positives of the Year 1 classroom: “You’ll have your own tray with your name on!”, “You’ll have your own chair and table space!”, “You’ll be able to play on the Key Stage 1 play equipment every day!” …

I think it’s fair to say, the children, their parents, my colleagues and myself all had a sense of closure when our time together came to an end, and we were all ready to move on to the next chapter.

I still don’t know what my next chapter will be – and I ‘have need of patience’. My belief in the potential of shared reading to build communities has not gone away, my motivation to work with children and families is as strong as ever, and my desire to remove obstacles that prevent children from learning to read remains.

I want to use my wide-open hands to:

Take off anxiety,

Take off stress,

Take off pressure,

Relax into reading,

Bond through books.

‘Do what you can,

with what you have,

where you are.’

Theodore Roosevelt

Follow the ‘Read with Julia’ blog

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.